Hip Dysplasia

Normal Hips, Early Dysplasia,

Moderate Dysplasia, Severe Dysplasia

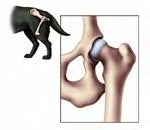

Hip dysplasia is a common and potentially debilitating joint disease in dogs. Although occurring in many canine lines, hip dysplasia most often affects large dog breeds. The Golden and Labrador Retrievers, German Shepherd Dogs, Rottweilers, and Chow Chows are particularly susceptible to hip dysplasia. Fortunately, there are a number of treatment options available for dogs afflicted with this painful and degenerative disease. Normal, healthy hip joint with a deep acetabular cup and healthy cartilage in the cup and on the ball of the femur.

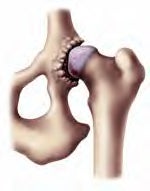

Note how the head of the femur sits tightly within the acetabulum. Early/Mild dysplastic hip with no degenerative changes. Note how joint laxity allows the head of the femur to subluxate. The acetabular cup may be abnormally shallow and the joint may exhibit laxity. This stage of hip dysplasia can often be treated with corrective surgery (see TPO in this brochure) before the disease progresses requiring more invasive and costly surgery. Moderate/ Severe hip dysplasia is recognized by the cartilage fibrillation and erosion on the ball of the femur and the acetabular cup. There is also a buildup of osteophytes (bone spurs and calcium deposits) around the rim of the acetabular cup.

This is a very painful joint that requires corrective surgery to alleviate the pain and return the joint to normal function. If corrective action is not taken then the dysplasia will inevitably progress to severe. Severe dysplasia is common in older dogs whose hip dysplasia has gone untreated for an extended period of time. This hip joint has severe arthritis. Note the flattening of the head of the femur and added bone fillings around the neck of the femur and within the acetabulum This dog's joint requires a total hip replacement to restore his quality of life and provide him with a pain-free, normal functional hip joint.

What is hip dysplasia?

Hip dysplasia is a developmental disorder affecting the coxofemoral (hip) joints in dogs. The problems associated with hip dysplasia stem from an imbalance in the muscle mass and mechanical forces which are centered on the hip joint. This imbalance is associated with excessive laxity (looseness) which is usually the result of a shallow acetabulum (cup).

When the hip joints exhibit laxity (looseness), the ball of the femur rides on the edge of the socket rather than gliding smoothly in the socket. This results in pain and eventually to the formation of abnormal calcium deposits, bone spurs and/or arthritis. Eventually, some hip joints will suffer either a partial or complete luxation.

Continued use of the affected joint causes abnormal wear on the joint's cartilage surfaces leading to further damage and a self-perpetuating degenerative process ensues.

Abnormal bony development of the hip joint often results, and inflammation and irritation (arthritis) ultimately cause mild to severe lameness. The joint capsule becomes inflamed and a subsequent increase in synovial fluid in the joint exacerbates the laxity.

These physiological changes should be dealt with early (between 4 and 8 months) to attempt to reduce the progress toward degenerative joint disease. The hallmark sign of degenerative joint disease is articular cartilage damage.

This results in the exposure of subchondral bone and pain nerve fibers resulting in significant joint pain. Once degenerative joint disease is present, there a fewer treatment options available.

Breeds Commonly Affected by Canine Hip Dysplasia

Airedale Terrier

Akita

Alaskan Malamute

American Bulldog

American Eskimo Dog

American Staffordshire Terrier

American Pit Bull Terrier

American Water Spaniel

Anatolian Shepherd Dog

Australian Cattle Dog

Australian Shepherd

Bearded Collie

Belgian Malinois

Bernese Mountain Dog

Bloodhound

Border Collie

Boxer

Bulldog

Bullmastiff

Chesapeake Bay retriever

Chinese Shar-Pei

Chow Chow

Clumber Spaniel

Curly-Coated Retriever

Dachshund

Dalmatian

English setter

Flat-coated retriever

German shepherd dog

German shorthaired pointer

German wirehaired pointer

Golden retriever

Great Dane

Great Pyrenees

Irish setter

Irish wolfhound

Keeshond

Labrador retriever

Mastiff

Neopolitan mastiff

Newfoundland

Norwegian Elkhound

Old English sheepdog

Pointer (English pointer)

Rhodesian ridgeback

Rottweiler

St. Bernard

Staffordshire Bull Terrier

Samoyed

Springer spaniel, English

Springer spaniel, Welsh

Vizsla

Weimaraner

The Genetics of Hip Dysplasia

The heritability of hip dysplasia has been firmly established. Several genes have been found to contribute to the ultimate size, shape, strength and growth potential of the hip joint. Furthermore, hip dysplasia is a genetically additive disease; the severity of the affliction is largely the result of a number of disease-related genes present in a particular animal.

The multitude of genetic and environmental factors that influence the transmission and development of hip dysplasia make it difficult to predict how the disease will be expressed. It is safe to say that breeding dogs between phenotypically normal dogs will generally result in more normal puppies than will breeding a dysplastic and normal dog or two dysplastic dogs to each other. However, studies have shown that even when both parents are phenotypically normal they can still produce offspring that are phenotypically dysplastic [1]. In spite of careful breeding efforts and the use of classifications from the Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA), such as breeding animals whose parents and grandparents were normal, the progress toward eradication of this disease has been frustratingly slow.

The OFA Hip Registry

The Orthopedic Foundation for Animal's Hip Registry is designed to provide a standardized criterion for evaluation of CHD and develop a multi-breed database. This database is used to develop selective breeding programs that reduce the prevalence of CHD. The OFA requires symmetrical radiographs of the pelvis. These radiographs are evaluated by three board certified radiologists and classified as excellent, good, fair, borderline, mild, moderate or severe. Excellent or good classifications on individuals older than 24 months receive a breed registry number. A preliminary evaluation may be performed as early as 4-5 months with 90% accuracy.

Environmental Factors and Hip Dysplasia

Environmental factors do not cause hip dysplasia but can significantly affect whether or not the condition will eventually manifest itself and to what degree. Environmental influences help explain the fact that only animals with a hip dysplasia genotype can develop the condition while not all animals with the genotype will exhibit the disease.

Nutrition in the young dog is one of the most studied exogenous elements affecting the development of hip dysplasia and may have a profound influence on the development of the disease. One study noted that only 33% of dogs that were fed ad libitum developed normal hips, whereas 70% of the dogs that were fed one quarter of the same diet developed normal hips. Another study in German Shepherds showed that 63% of the dogs weighing more than the mean, developed dysplastic hips.

In contrast, 37% of the dogs that weighed less than the mean developed dysplastic hips [2]. Puppies that are genotypically susceptible to canine hip dysplasia will exhibit an increased incidence and severity if placed on a high caloric diet. These studies strongly suggest that limiting caloric intake in young, growing dogs (especially the larger at risk breeds) is beneficial in preventing the development of canine hip dysplasia.

Clinical Signs of Hip Dysplasia

Dogs suffering from hip dysplasia are often reluctant to jump or rise from the rear legs, exhibit abnormal locomotion and may hesitate to climb and descend stairs. Young dogs in the age range of five to ten months may exhibit pain when the hips are extended. In addition, there may be evidence of decreased muscle mass and a reduced range of motion. Many of these young dogs have a torn round ligament and a significantly stretched joint capsule. Clinical signs often do not correlate well with radiographic changes in young dogs.

Environmental factors such as diet and excessive exercise play an important role in the development of hip dysplasia. Ask your veterinarian for recommendations on diet and exercise. Over 110 dog breeds have been identified with hip dysplasia. About 95% of dogs with hip dysplasia are affected in both hip joints.

Diagnosing Hip Dysplasia

Hip evaluations must not be delayed until two years of age (especially in susceptible breeds), but should be performed as young as five to six months old. Cup depth and joint laxity should be assessed and dogs that exhibit irregularities should be identified as soon as possible. Radiographs are utilized to confirm the presence of joint laxity in young dogs and the presence of degenerative joint disease in the older patient. Joint laxity without associated arthritis is most common in dogs between four and twelve months old and can be difficult to diagnose through x-rays.

Using a technique called palpation and hip manipulation, veterinarians can often detect hip dysplasia before symptoms become evident and when radiographs fail to identify malformations (Table 1, below). In a palpation exam, the rear leg is extended to test the hip's range of motion. Another part of a palpation exam requires that the dog be anesthetized (see diagram, right) to allow the hip to be palpated without the dog holding the hip in its socket using its muscles creating a false negative result.

During this palpation the veterinarian can assess the laxity of the hip by measuring the angle that the hip subluxates and the angle that it reduces. These angles are important in deciding the available treatment options. Palpation also allows for early detection of hip dysplasia which gives the dog a better chance for a normal life without the need for a total hip replacement.

Palpation Exam

Using a technique called palpation and hip manipulation, veterinarians can often detect hip dysplasia before symptoms become evident and when radiographs fail to identify malformations. Moving the knee towards the center causes the hip to fall out of its socket (subluxate). Moving the knee away from the center causes the hip to return to the socket (reduction). These two actions allow the veterinarian to measure the corresponding angles which indicate the amount of joint laxity.

Penn Hip Certification

The Penn Hip system was developed to provide a reliable method for predicting the development of CHD. Proponents of this system claim disappointing results in traditional method for reducing the prevalence of CHD. This system can be used in dogs as early as 16 weeks of age. It is based on quantitatively measuring joint laxity and helps identify susceptible individuals before degenerative changes are present.

The Penn Hip method uses three separate radiographs, taken under deep sedation or general anesthesia. They include a distraction view, a compression view for evaluating joint laxity, and a hip-extended view for evaluating degenerative changes. The degree of laxity reported as a distraction index (0 to 1 with 0 being tight) is an important risk factor in determining whether a dog will develop CHD. The more laxity as indicated by a higher distraction index, the greater the chance of developing CHD.

This information can be used for decisions about breeding, life style for the dog and potential surgery.

Table 1: Effective Diagnosis of Hip Dysplasia Age Palpation Radiographs

6 months 75% 25%

1 year 50% 50%

1.5 years 25% 75%

2 years 0% 100%

Treatment Options: Medical Management

Prompt and early diagnosis of canine hip dysplasia increases the number of available treatment options and thus helps prevent the pain and arthritis that accompany the advanced disease. Medical management may control the clinical signs of some dogs with hip dysplasia.

Treatment is directed at reducing cartilage wear and slowing the progress of degenerative joint disease. Pain control agents, such as nonsterioidal anti-inflammatory drugs and chondroprotective agents, are typically used to manage the disease. Dietary alterations to control growth in young dogs and weight in older dogs are crucial in the medical management of hip dysplasia. The analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects of medical management unfortunately may only mask the development of a degenerative condition and may not be the best course action to ensure a favorable outcome.

Owners of dogs with dysplastic hips should also be advised that while medical therapy may be an effective short-term relief, it may allow progress of the disease to the point where only salvage-level surgical procedures are possible. Therefore, if medical management is pursued, close clinical and radiographic monitoring of the condition is imperative in order to prevent closing windows of opportunity for surgical options.

Treatment Options: Surgical Management

Surgical management of canine hip dysplasia, especially if performed early in the course of the disease, improves the prognosis for a long-term acceptable joint function. Surgical management is pursued if medical management is no longer successful in controlling the clinical and radiographic signs, if the owner is concerned with the long-term comfort and limb function for the dog, if the dog is intended to perform an athletic function and to slow or stop the progress of degenerative joint disease in the young dog.

Triple Pelvic Osteotomy (TPO) The triple pelvic osteotomy was developed for patients in the early stages of canine hip dysplasia who exhibit minimal degenerative changes in their hip joints. This procedure significantly reduces hip laxity by rotating the cup further over the ball of the femur and thereby curtailing the painful onset of degenerative joint disease by creating a more normal joint environment.

In performing this procedure, the veterinary surgeon cuts the pelvis to allow rotation of the acetabulum further over the ball of the femur. The rotated pelvis is then stabilized by a specially designed surgical implant (Figure X). If the disease is bilateral, both hips will require surgery. The two surgeries are typically staged, however, in the time it takes for the first hip to recover from surgery, the disease continues to progress in the other hip and can often preclude the option to salvage the dog's own hip.

Postoperative care for dogs that have undergone pelvic osteotomy involves antibiotic administration, exercise restriction, physical rehabilitation and a rest period to ensure adequate healing of the surgical site. Routine postoperative examinations by a veterinarian, including pelvic radiographs, are essential to evaluate the recovery process.

Total Hip Replacement (THR) Total hip replacement involves the replacement of the diseased hip joint with a hip prosthesis. This surgery may be performed at any stage of hip dysplasia but is most appropriate in patients who have the latter stages of degenerative joint disease or severe luxation. Radiographic changes including flattened femoral heads, shallow acetabulum and bony osteophytes are the classic signs of degenerative joint disease.

These patients are not suitable candidates for pelvic osteotomy because of the presence of degenerative joint disease and the lack of a normal joint surface. Total hip replacement is considered by many surgeons as the gold standard for the treatment in advanced canine hip dysplasia. THR patients experience an excellent success rate and usually recover fully from their surgery and lead active, athletic lives.

Postoperative care of a total hip replacement patient typically involves antibiotic administration, exercise restriction, physical rehabilitation and rest for a few weeks. The dog is monitored on a regular basis using pelvic radiographs to ensure that all implants have been well seated and the prosthesis is functioning well.

Surgical Management

Triple Pelvic Osteotomy (TPO) for the treatment of hip dysplasia. A specially designed surgical implant stabilizes the pelvis after being rotated 25-35 degrees to better capture the ball of the femur in the acetabular cup.

"Dr. Rooks and the Triple Pelvic Osteotomy technique that he developed altered the future of Kodiak's life" Total Hip Replacement (THR) for the treatment of moderate to severe hip dysplasia. This procedure involves the removal of the dog's diseased hip joint and replacing it with a fully functional prosthesis.

Femoral Head and Neck Excision Arthroplasty This salvage procedure is utilized for dogs whose owners may have limited financial means that hope to improve the quality of life for their dog. The best candidates for this procedure are dogs that weigh less than 40 pounds.

During femoral head and neck arthroplasty no rotation of the acetabulum is attempted and no implants are installed. Instead the femoral head and neck are simply removed to alleviate the pain associated with joint articulation (Figure X). The joint space is then allowed to fill with fibrous connective tissue that serves as a pseudoarthrosis or a joint. Although many dogs appear to have normal function after femoral head and neck excision arthroplasty, it is difficult to evaluate the degree of discomfort associated with the procedure.

These patients typically exhibit a reduced range of motion but this may be minimized through the use of physiotherapy including passive motion, swimming and other physiotherapy techniques. Postoperatively, antibiotics are administered for the first few days after surgery, but unlike the other procedures exercise may not be restricted and in fact the clients are instructed to flex and extend their dog's hips.

Juvenile Pubic Symphysiodesis (JPS) This surgical procedure is performed on puppies whose hips exhibit abnormal amounts of laxity. It involves the use of electrocautery to prematurely close the pubic symphysis. The remainder of the pelvis continues to grow and the closed pubic symphysis forces the hip socket to rotate into a more normal alignment.

The surgery must be performed before 20 weeks of age and best if done between 12-18 weeks as it relies on growth of the pelvis to be effective.

References:

Lust, G., An Overview of the Pathogenesis of Canine Hip Dysplasia, JAVMA, Volume 210, Number 10, p. 1445. May 15, 1997. Kealy, R.D., et al., Effects of Limited Food Consumption on the Incidence of Hip Dysplasia in Growing Dogs, JAVMA, Volume 201, Number 6, p. 857

© 2002 All-Care Animal Referral Center All rights reserved.

Also

Hip dysplasia literally means an abnormality in the development of the hip joint. It is characterized by a shallow acetabulum (the "cup" of the hip joint) and changes in the shape of the femoral head (the "ball" of the hip joint). These changes may occur due to excessive laxity in the hip joint.

Hip dysplasia can exist with or without clinical signs. When dogs exhibit clinical signs of this problem they usually are lame on one or both rear limbs. Severe arthritis can develop as a result of the malformation of the hip joint and this results in pain as the disease progresses. Many young dogs exhibit pain during or shortly after the growth period, often before arthritic changes appear to be present. It is not unusual for this pain to appear to disappear for several years and then to return when arthritic changes become obvious.

Dogs with hip dysplasia appear to be born with normal hips and then to develop the disease later. This has led to a lot of speculation as to the contributing factors which may be involved with this disease. This is an inherited condition, but not all dogs with the genetic tendency will develop clinical signs and the degree of hip dysplasia which develops does not always seem to correlate well with expectations based on the parent's condition. Multiple genetic factors are involved and environmental factors also play a role in determining the degree of hip dysplasia. Dogs with no genetic predisposition do not develop hip dysplasia.

At present, the strongest link to contributing factors other than genetic predisposition appears to be to rapid growth and weight gain. In a recent study done in Labrador retrievers a significant reduction in the development of clinical hip dysplasia occurred in a group of puppies fed 25% less than a control group which was allowed to eat free choice. It is likely that the laxity in the hip joints is irritated by the rapid weight gain. If feeding practices are altered to reduce hip dysplasia in a litter of puppies, it is probably best to use a puppy food and feed smaller quantities than to switch to an adult dog food. The calcium/phosphorous to calorie ratios in adult dog food are such that the puppy will usually end up with higher than desired total calcium or phosphorous intake by eating an adult food. This occurs because more of these foods are necessary to meet the caloric needs of puppies, even when feeding to keep the puppy thin.

If clinical signs of hip dysplasia occur in young dogs, such as lameness, difficulty standing or walking after getting up, decreased activity or a bunny-hop gait, it is often possible to help them medically or surgically. X-ray confirmation of the presence of hip dysplasia prior to treatment is necessary. There are two techniques currently used to detect hip dysplasia, the standard view used in Orthopedic Foundation for Animals (OFA) testing and X-rays (radiographs) utilizing a device to exaggerate joint laxity developed by the University of Pennsylvania Hip Improvement Program (PennHIP). The PennHIP radiographs appear to be a better method for judging hip dysplasia early in puppies, with one study showing good predictability for hip dysplasia in puppies exhibiting joint laxity at four months of age, based on PennHIP radiographs.

Once a determination is made that hip dysplasia is present, a treatment plan is necessary. For dogs that exhibit clinical signs at less than a year of age, aggressive treatment may help alleviate later suffering. In the past a surgery known as a pectineal myotomy was advocated but more recent evidence suggests that it is an ineffective surgical procedure. However, administration of glycosaminoglycans (Adequan Rx) may help to decrease the severity of arthritis that develops later in life. Surgical reconstruction of the hip joint (triple pelvic osteotomy) is helpful if done during the growth stages. For puppies with clinical signs at a young age, this surgery should be strongly considered. It has a high success rate when done at the proper time.

Dogs that exhibit clinical signs after the growth phase require a different approach to treatment. It is necessary to determine if the disorder can be managed by medical treatment enough to keep the dog comfortable. If so, aspirin is probably the best choice for initial medical treatment. Aspirin/codeine combinations, phenylbutazone, glycosaminoglycosans and corticosteroids may be more beneficial or necessary for some dogs. It is important to use appropriate dosages and to monitor the progress of any dog on non-steroidal or steroidal anti-inflammatory medications due to the increased risk of side effects to these medications in dogs.

If medical treatment is insufficient then surgical repair is possible. The best surgical treatment for hip dypslasia is total hip replacement. By removing the damaged acetabulum and femoral head and replacing them with artificial joint components, pain is nearly eliminated. This procedure is expensive but it is very effective and should be the first choice for treatment of severe hip dyplasia whenever possible. In some cases, this surgery may be beyond a pet owner's financial resources. An alternative surgery is femoral head ostectomy. In this procedure, the femoral head (ball part of the hip joint) is simply removed. This eliminates most of the bone to bone contact and can reduce the pain substantially. Not all dogs do well following FHO surgery and it should be considered a clear "second choice".